Future Fossils

When the two of us first began research for a course on conservation in South Africa, we didn’t know we would focus on rhinos. On a sunny, dusty winter’s day, at a rest stop surrounded by fruit stands and unfamiliar, swaying trees, we talked for over an hour, trying, without success, to pin down exactly what this story would become.

The next morning, in the pale dawn light of our first game drive into the bush, we saw a mother and baby white rhinoceros. The mother was protective; the baby was rambunctious.

All doubt vanished. The story was about the rhinos.

Humans and rhinos are inextricably intertwined. A desperate poacher and a wealthy tourist keen on sighting the iconic animal often cross the same tracts of land. The immense economic inequalities in South Africa today have been centuries in the making, but time is running out for this politically and socially charged conservation effort.

This effort is influenced by complex and often conflicting interactions between private reserves, the South African government, and marginalized black communities living alongside the rhinos' habitat. Without a range of strategies, especially ones that emphasize local engagement, South Africa’s wild rhinos may go the way of the dinosaurs within the next few decades or sooner.

The poaching crisis is an ongoing issue in South Africa, which is home to 75% of the world’s remaining rhinos—fewer than 19,000 of the white rhino, and fewer than 2,000 of the black rhino. Although poaching abated for a period between 1990 and 2007, a number of factors have reversed that trend. Rhino poaching in South Africa has escalated sharply over the last ten years, from one rhino killed per month in 2007 to about three per day as of 2017.

A rhino’s horn is made of keratin, just like human hair and fingernails, and like fingernails, it can regrow if cut off away from the base. Rhino horn has long been a commodity in Vietnam and China, where it is a status symbol and an ingredient for traditional medicine. The black market price remains more valuable than its weight in cocaine or gold.

A rhino’s horn is made of keratin, just like human hair and fingernails, and like fingernails, it can regrow if cut off away from the base. Rhino horn has long been a commodity in Vietnam and China, where it is a status symbol and an ingredient for traditional medicine. The black market price remains more valuable than its weight in cocaine or gold.

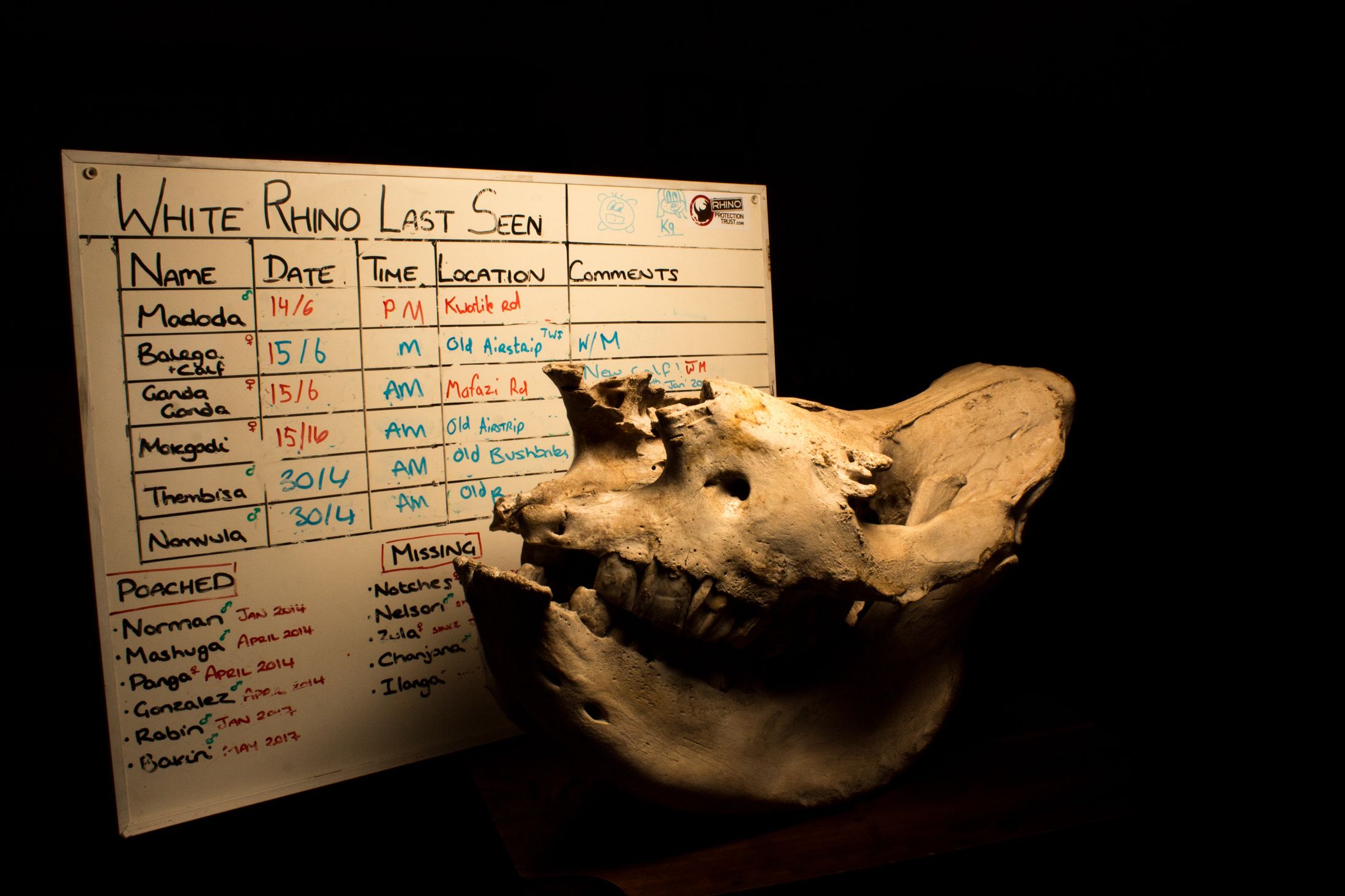

We felt the phantom, driving force of international crime syndicates throughout our time in the field. We waited at security checkpoints in our safari vehicles as armed guards checked for weapons or smuggled items. At our research camp, we saw skulls of rhinos whose horns had been brutally hacked off, cracking the bone. We were told not to post any images of rhinos to social media, since our phones’ geotagging features might send up a virtual flare with the animals’ location. We never saw any members of that criminal world, but they felt present, as if they were just beyond a fence we couldn’t see.

Rhino horn has long been a commodity in Vietnam and China, where it is both a status symbol and an ingredient for traditional medicine. Demand for the horn has surged alongside the growing middle classes in these countries. In 2015, the European Union Action to Fight Environmental Crime (EFFACE) estimated through a trade monitoring network that “the street price of rhino horn is $100,000/kg...with a single horn weighing between 1-3 kg.” In 1990, the price for that same horn was only $250/kg. Today, the black market price of rhino horn remains much more valuable than its weight in cocaine or gold.

Rhino horn trade is restricted through regulations at an international level. The Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) banned international sale and purchase of rhino horn in the 1970s, although governments affected by poaching have their own jurisdiction regarding the domestic horn trade. This means that possession of horn is still legal within South Africa, and the criminal act occurs when moving it out of the country.

The battle to protect the fewer than 19,000 remaining white rhinos and fewer than 2,000 black rhinos in South Africa is especially fierce because of rhinos' importance for tourism. South Africa boasts 74% of the world’s remaining rhinos, and it pays off: the tourism industry employs over half a million people, according to the European Union Action to Fight Environmental Crime.

The battle to protect the fewer than 19,000 remaining white rhinos and fewer than 2,000 black rhinos in South Africa is especially fierce because of rhinos' importance for tourism. South Africa boasts 74% of the world’s remaining rhinos, and it pays off: the tourism industry employs over half a million people, according to the European Union Action to Fight Environmental Crime.

That incentive, so high due to the extraordinary black market price, has led to increasingly sophisticated tactics from organized crime. On the ground, poachers use high-caliber rifles and helicopters. They bribe or involve wildlife professionals, drivers, and pilots. On an international level, ineffective and often corrupt border control also contributes to the carnage: “lax enforcement on the Mozambican side has meant that Mozambican poaching gangs are responsible for a large portion (some estimate up to 90 percent) of rhino killings in Kruger Park.” Some transactions may even pass through institutions of countries that appear far removed from the poaching crisis, including the United States. CSIS has suggested that this may create “a powerful opportunity for U.S. policymakers and enforcement agencies seeking to...disrupt the illicit wildlife trade.”

Although we were students, distanced from the darkest parts of the poaching world, we discovered firsthand the thrill of being dropped into a completely new environment. Every morning in the blue-grey dawn, huddling under blankets to hide from the chill of the whipping wind, we were tourists, just like the many visitors who flock to safari getaways from faraway towns and offices. And just like those visitors, we were on the edge of our seats as we heard the crackling voices of our guides on the radio. But each animal sighting required patience. We could easily imagine the bleary-eyed disappointment of a future tourist, stuck in the lull of looking for a creature that might one day be far too rare to find.

The other great economic value of rhino horn is its allure for safari tourists who hope to see it on living rhinos; international and South African visitors alike flock to reserves and parks each year to see rhinos, as well as the other “Big Five” game animals. In addition, tourism employs over half a million people. If all rhinos went extinct, it would cause South Africa an estimated 79 to 118 billion euro loss in wildlife tourism income.

Even if rhinos do not face absolute extinction, their continued decline still dramatically affects the tourism industry, with EFFACE estimating that each 1% reduction in the rhino population causes about a billion euro loss. In addition, EFFACE notes that “as poaching decreases wildlife populations, it also negatively affects the touristic experience as it changes animal behaviour (animals become shyer and more difficult to locate) and instils fear and safety concerns among visitors and gives countries a bad reputation.”

We visited Enable, one of the nearest villages to Makalali Private Game Reserve, on our first day in the field. We crossed bumpy dirt roads until we encountered a different kind of flora and fauna: herds of donkeys, shepherded alongside the road with clanging bells around their necks; chickens and goats, intermingled in small backyards; dry bushes providing little cover from a surprisingly strong winter sun.

Our meeting took place in an outdoor pavilion formed with wooden beams and a tin roof, in a circle of plastic chairs. Four of us, as guests, faced the induna (chief) and his family, many of whom also serve as his advisors. Just a few miles from the mother and baby rhino we had seen that morning was a whole community of people separated from those rhinos—by fence lines, and also by a lack of communication between the groups on either side.

Communities on the fringes of parks and reserves rarely see economic benefits from either the trade of rhino horn or from the lucrative and white-dominated tourism industry. High unemployment rates and lack of access to basic necessities create a high economic incentive for would-be poachers. This woman in Enable is washing clothes with water from a makeshift well, because the borehole necessary to provide a reliable supply of water to the village is within the borders of the nearby private game reserve. No actions have yet been made to connect the borehole to the community.

Communities on the fringes of parks and reserves rarely see economic benefits from either the trade of rhino horn or from the lucrative and white-dominated tourism industry. High unemployment rates and lack of access to basic necessities create a high economic incentive for would-be poachers. This woman in Enable is washing clothes with water from a makeshift well, because the borehole necessary to provide a reliable supply of water to the village is within the borders of the nearby private game reserve. No actions have yet been made to connect the borehole to the community.

Perhaps the most complex factor reinforcing the continued cycle of poaching is the relationship between wildlife reserves and local communities. Communities on the fringes of parks and reserves rarely see economic benefits from either the trade of rhino horn or from the lucrative and white-dominated tourism industry. High unemployment rates and lack of access to basic necessities create a high economic incentive for would-be poachers.

Conversely, local community members often don’t have the chance to develop a sentimental or cultural connection to animals like rhinos because they are economically shut out from learning about or even glimpsing these creatures. Thomas Moakamaa, one of the induna’s relatives and our de facto translator, explained that some members of his community have traditionally linked their identities with wildlife:

We definitely want them [the animals]: some people are saying they are elephants...you find a particular family saying we are lions, we are warthogs, we are cheetahs, all these kind of big animals. They feel they are associated, but we are discouraged by the fact that we don’t know them. We are not having access to them.

John Mafogo, the induna, is soft spoken but firm. As Thomas translated for him, we learned that he does not think the reserves care much about his community, and wants to establish a committee that regularly interacts with reserve owners. Thomas also described how the community leaders felt that many reserve owners only come to local communities like Enable under suspicion of poaching. “It’s an attitude of ‘there’s nothing I need from the poor,’” he told us. “We have never seen the Big Five, even though we are neighbors. The main intention [from the reserves] is to make money, but we crave a relationship.”

But reserve owners can also feel an immense distrust when it comes to these relationships, as they sometimes find that one instance of misplaced faith can leave an opening for poachers. One private reserve owner told us his view on nearby communities: “These people, they just live for today...if they can’t make a living, what choice do they have [but to poach]?” Or, in other cases, they don’t see anything wrong with the status quo; they simply believe that the relationship local communities like Enable yearn for already exists. As the same reserve owner put it: “It’s a normal neighbor relationship. He [the induna] knows we’re giving his people jobs.” And: “Trust is a mutual thing...when you have too many people, there’s lots of hidden agendas.”

We saw rhinos in three other encounters during our three weeks in Makalali and Kruger National Park. Once, we were merely feet away from three resting white rhinos, lying in the shade of a tree as oxpeckers fluttered around them. The next time, we peered through the trees at two white rhinos ambling through a river valley. In Kruger, we were given barely a glimpse of a rhino’s back, almost as still as a large boulder stationed between tall yellow stalks. Every time, our hearts thumped with anticipation.

But at each sighting we had learned more about their crisis, too, and it almost seemed like they were slipping away. So we were grateful when we met the people who told us about their personal stake in the problem, and shared their ideas for the future. It reassured us that maybe we could come back, and look for the rhinos again.

Philip Kussler is an advocate for legalizing the rhino horn trade and the co-owner of a private reserve with several white rhinos. He’s a tall, imposing man with a sunglasses tan, focused blue eyes, and passionate views. “I can tell you exactly why we are failing all the time [at stopping poaching],” he declared confidently. Philip believes that banning the horn trade isn’t effective. Instead, allowing the international sale and purchase of rhino horn would flood the market with product, lowering the value of the horn and therefore the incentive to poach. When asked what he thinks about current anti-poaching efforts, he insisted that “we don’t have much time to keep trying things that aren’t working.”

“The only way we can save the rhino is by legalizing the horn trade.” Philip Kusseler is a private reserve owner near Makalali who advocates for a controversial solution to the poaching problem: allowing the international sale and purchase of rhino horn. Philip has also proposed sharing rhino ownership between reserve owners like himself and neighboring locals. He hopes the collaboration would create a legal avenue for struggling communities to reap the profits associated with rhinos.

“The only way we can save the rhino is by legalizing the horn trade.” Philip Kusseler is a private reserve owner near Makalali who advocates for a controversial solution to the poaching problem: allowing the international sale and purchase of rhino horn. Philip has also proposed sharing rhino ownership between reserve owners like himself and neighboring locals. He hopes the collaboration would create a legal avenue for struggling communities to reap the profits associated with rhinos.

Rhino horn can be trimmed and regrown every few years, much like human fingernails, so there is no need to kill the animals to sell horn. John Hume, who owns the largest legal rhino farm in South Africa, recently had an auction attempting to sell some of his horn product within South Africa’s borders. The auction fell flat. Philip believes that’s simply because there won’t be an incentive to acquire the commodity until it can be sold at high value internationally. So for now, those who do own horn—either by owning live rhinos or by safely harvesting it—essentially have to wait.

Both sides of the poaching conflict use skilled trackers to gain the upper hand. In addition to traditional tracking methods like scat and track marks, modern poachers can also locate rhinos with GPS coordinates from photographs, leading some reserves to forbid tourists from posting rhino photos on social media.

Both sides of the poaching conflict use skilled trackers to gain the upper hand. In addition to traditional tracking methods like scat and track marks, modern poachers can also locate rhinos with GPS coordinates from photographs, leading some reserves to forbid tourists from posting rhino photos on social media.

In the meantime, the fight is on in full force. Military-style groups have mobilized in a number of different forms, from the standard anti-poaching units (APUs, for short) to expert trackers, K9 units, and unarmed community-enlisted anti-poaching patrols. Safari guide and master tracker Patson Sithole, usually a jovial, bright-eyed figure, lowered his voice when he told us about becoming involved in the poaching fight. "Following these tracks, it’s dangerous,” he warned. “If [poachers] see you before you see him, you are a dead man.” And Pete Wearne, a K9 APU member, reminded us that the fight is not just physical but emotional as well. “I know every single rhino, its name, where it lives. When one does get poached, there’s a personal connection. That’s the worst thing about it.”

“I know every single rhino, its name, where it lives. When one does get poached, there’s a personal connection. That’s the worst thing about it.”

Pete Wearne, K9 anti-poaching unit

But this fight isn’t always a traditional war. The Black Mambas, an organization with a multi-pronged volunteer, research and security approach, is a unique group of powerful women in camouflage. These all-female, unarmed agents gather horn trafficking intelligence and track poachers’ locations. The Mambas’ work is dangerous; without weapons, they rely on intense training in the bush, precise knowledge of the environment, and strategic placement in communities. They not only serve as eyes and ears for other APUs but also use the data they collect to make predictive models about high-risk poaching areas.

The Black Mambas are an all-female group of unarmed agents who gather horn trafficking intelligence and track poachers’ locations. The organization was created for women’s empowerment, and recruits from communities near private reserves.

The Black Mambas are an all-female group of unarmed agents who gather horn trafficking intelligence and track poachers’ locations. The organization was created for women’s empowerment, and recruits from communities near private reserves.

Programs like the Black Mambas recognize that rhino poaching is not only a conservation crisis, but also an intractable social problem that requires a stake in the community. “We are mothers,” emphasized Marble Madhlope, the manager of the Black Mambas organization. “When we started this, people were not believing in us. Now we are role models.”

Local conservationists emphasize that education is critical to fight the factors that compel locals turn to poaching in the first place. Kuttulo Shai, a lifelong conservationist who is now the camp manager of a private lodge called Mvubu, told us that he only ever got to see wild animals as a child because he won a contest in school. “I don’t think I would be here if I didn’t go on that game drive,” he says. “When I saw the fence, I thought only white people could go in there and black people could stay out. That was my perception.”

One rhino conservation group, Rhino Revolution, is spearheading multiple initiatives to reach children early on; they institute environmental education classes in local government primary schools and also create immersive learning experiences by funding buses for field trips much like the one Shai went on.

Karabo Mawele embodies the successes of community-based programming. She is currently finishing a three-year contract with Rhino Revolution, the first organization to release rehabilitated rhinos back into the wild. She lives in Rooibok-Laagte, about 20 kilometers from Kruger National Park, and cites the educational outreach program as the reason for her pursuing her goal of becoming a big game veterinarian. “At first I wanted to be a doctor,” she recalls, but says she changed her mind when she “got contact with the reserves.”

Karabo Mawele embodies the successes of community-based programming. She is currently finishing a three-year contract with Rhino Revolution, the first organization to release rehabilitated rhinos back into the wild. She lives in Rooibok-Laagte, about 20 kilometers from Kruger National Park, and cites the educational outreach program as the reason for her pursuing her goal of becoming a big game veterinarian. “At first I wanted to be a doctor,” she recalls, but says she changed her mind when she “got contact with the reserves.”

But education isn’t limited to the young. SANParks, South Africa’s national parks system, has an outreach program that invites sangomas, or traditional healers, to visit reserves and gain a broader context on the poaching environment. Since both poachers and anti-poachers seek out muti, or medicine that grants strength, to aid them on their missions, reaching sangomas could be one key to initiating community change.

Traditional healers, or sangomas, can play a role in both sides of the conflict near poaching hotspots. Although many people now rely on doctors for health care, some also continue to visit sangomas to seek cures for everything from domestic problems to infertility. Both poachers and anti-poachers seek out muti, or medicine that grants strength, to aid them on their missions.

Traditional healers, or sangomas, can play a role in both sides of the conflict near poaching hotspots. Although many people now rely on doctors for health care, some also continue to visit sangomas to seek cures for everything from domestic problems to infertility. Both poachers and anti-poachers seek out muti, or medicine that grants strength, to aid them on their missions.

Outlining the future, Shai emphasized this: “You can poach this rhino and get this much [money], or you can leave the rhino and all your families can work for 25 years. You give them the choice. I think if we show them the positives…but it will be hard to stop the poachers.”

In Johannesburg, a city pocked with ghost skyscrapers and still haunted by the legacy of the apartheid regime, rhinos are out of sight but not entirely out of mind. From the largest international policies to the classrooms of local villages to the murals of Johannesburg, rhino advocates are now at a crossroads, as they determine how to make conservation decisions while also factoring in human issues.

But the threat of extinction looms large. 1,028 South African rhinos were killed in 2017 alone for their horns. If nothing changes within the next few decades, South Africa’s wild rhinos may soon go the way of the dinosaurs.

***

Sierra Garcia is a master’s student in Environmental Communication at Stanford University.

Melina Walling is a junior studying English at Stanford University.

Original photos and story created in 2018.

This story was made possible by Stanford's Bing Overseas Studies Program and with guidance from Susan McConnell, Sebastian Kennerknecht, Julia Mason, Robin Van Den Berg, and Claudia Schnell. Please contact sgarcia3@stanford.edu or mwalling@stanford.edu with questions or comments about the story.